It’s been 34 years since the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act, a fully codified victory for those with physical disabilities. As our awareness grows about individuals with learning disabilities, memory issues, sight, and hearing losses among others, we, as designers and makers of human context, are charged with a mission to make our environments supportive of all.

Earlier this year, I presented at a conference, ”Inclusive Design: Rationale + Practice,” with two distinguished practitioners: Valerie Fletcher, executive director at the Institute for Human Centered Design, a not-for-profit centered on the role of design in social equity across the spectrum of ability, age and culture, and Ian Law, RLA, a registered landscape architect and senior project manager with Fuss & O’Neill, Inc.

“Inclusive Design: Rationale + Practice” presented at the Women Who Build Summit.

Valerie presented a shocking statistic: When it comes to sensory, physical, and brain-based functions, a majority of the population falls somewhere between “highly disabled” and “completely disabled.” With ADA as a baseline, inclusive design is meant to address everyone across that spectrum. She noted that “Inclusive (Universal) Design starts with accessible design and calls for a more creative and imaginative process to create places and programs that will work seamlessly for the widest possible group of people. The goal is to eliminate disabling environments (physical, information, communication, social and policy environments) in favor of enabling ones for everyone.”

For example, a very small portion of the population is fully blind, but a large number of people have some form of visual impairment. Very few people actually read braille, yet it’s used everywhere. Inclusive design would focus not only on universal design (following ADA, code requirements), but would do more to help those with visual impairments. Signage might be designed with higher text contrast, larger font, and additional signs or symbols to assist with wayfinding.

The Young Classroom at Smith College was designed for all types of learners.

Amenta Emma recently had the privilege of working with Smith College on a classroom model to serve a neurodiverse student population, including those with dyslexia, autism, ADHD, and other learning challenges. We organized the 6,000 SF classroom space around a central large room with an array of technology and writing surfaces on all sides. Central to the support for neurodiverse learners, we provided an element of choice for students – spaces within the space that could best fit differing learning styles and preferences. Introducing the agency of choice, while still being predictable, and mitigating common distractions such as reflectivity, bold colors, strong pattern contrast, and noisy crowds became crucial design drivers to creating an inclusive environment.

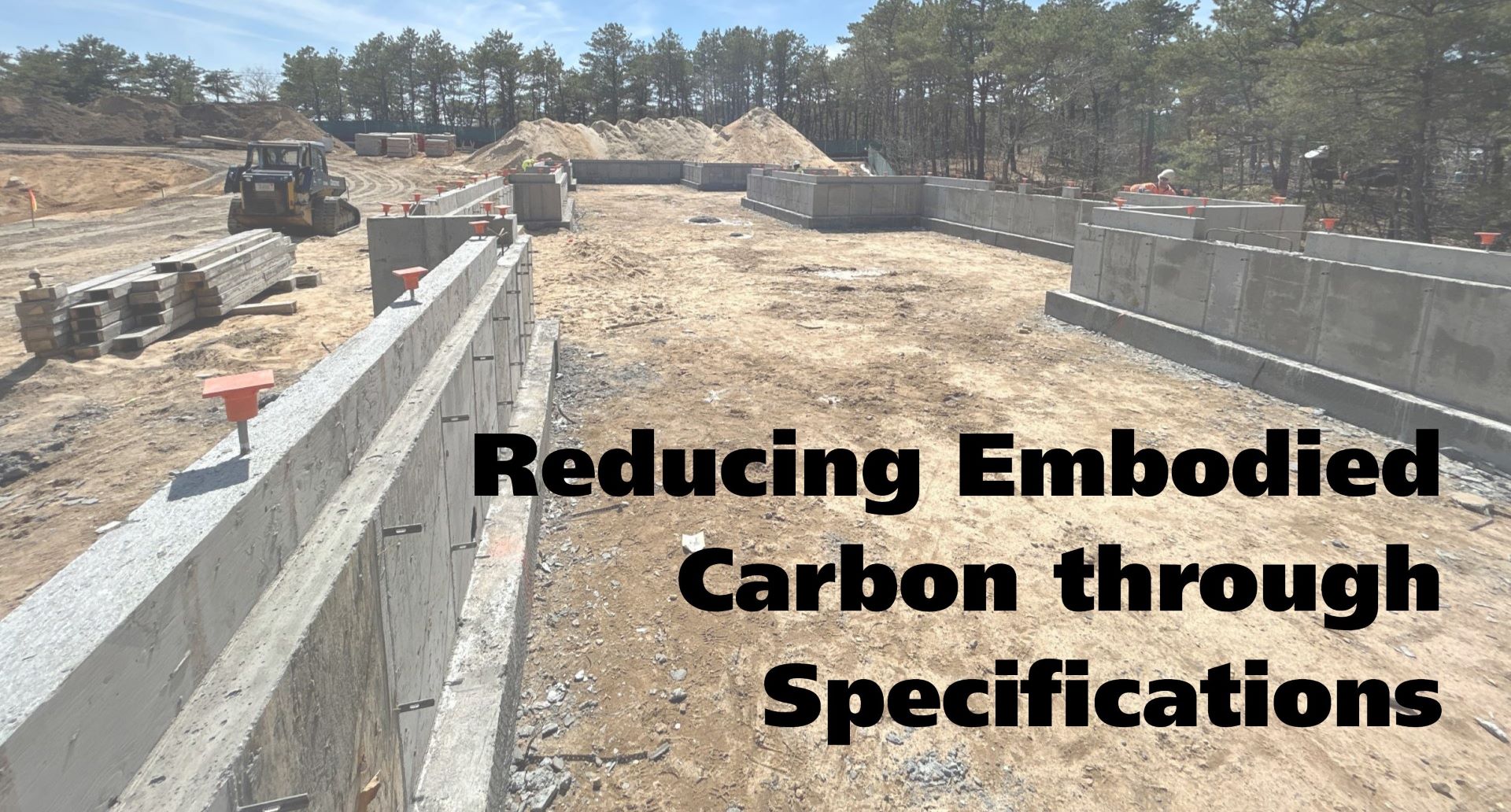

In the design of a memory facility at Avery Heights in Hartford, CT., we focused on a “small house” concept, breaking the open great room into five zones (communal dining, intimate dining, country kitchen, fireplace, and TV/book nook), while also maintaining a flexible, light, and open feel for larger group activities. We included a separate but visually connected room for quiet reflection and downtime to include aromatherapy and soothing music and outfitted with cozy furniture. We also integrated a discreet entry sequence for visitors to prevent patient distraction, and a two-zone outdoor garden space visible to staff from the common space for both social and reflective activity.

The Burnham Family Memory Care Residence at Avery Heights

There are so many examples of how inclusive design plays a role in our day-to-day. Transit-oriented development and downtowns with a sense of place enable people with easier access to employment in a safe, walkable, connected living environment. Spaces that allow individuals to age in place and stay connected to their communities utilize tech/tools like Smart phones, Smart Door Locks, Smart TVs, Nest thermostats, Alexa, Grandpads, etc.

Inclusive (Universal) Design starts with accessible design and calls for a more creative and imaginative process to create places and programs that will work seamlessly for the widest possible group of people. The goal is to eliminate disabling environments (physical, information, communication, social and policy environments) in favor of enabling ones for everyone.

The concept can be summed up very quickly: people first!