The focus on creating inclusive spaces that support a variety of personalities, needs, and abilities has become an increasing focus of architectural design. Historically, architects – through efforts like ADA and Universal Design – have focused on addressing physical ability in the design of the built environment. As our conception and awareness of diversity and inclusivity grows, we must consider broader concepts in the effort to create spaces of belonging. One of those emerging concepts is neurodiversity.

Neurodiversity recognizes that people experience and interact with the world around them in different ways. The idea is there is no “correct way” for the brain to work. Instead, there is a broad range of ways people perceive and respond to the world, and these differences are to be embraced and encouraged. The term neurodiversity was coined in the 1990s by Australian sociologist Judy Singer to promote equality and inclusion of “neurological minorities” that most commonly include people with autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and learning disabilities. The neurodiversity movement promotes these differences not as deficits, but rather as normal and potentially valuable variations on the way brains work. An estimated 15-20 percent of the world’s population exhibits some form of neurodivergence.

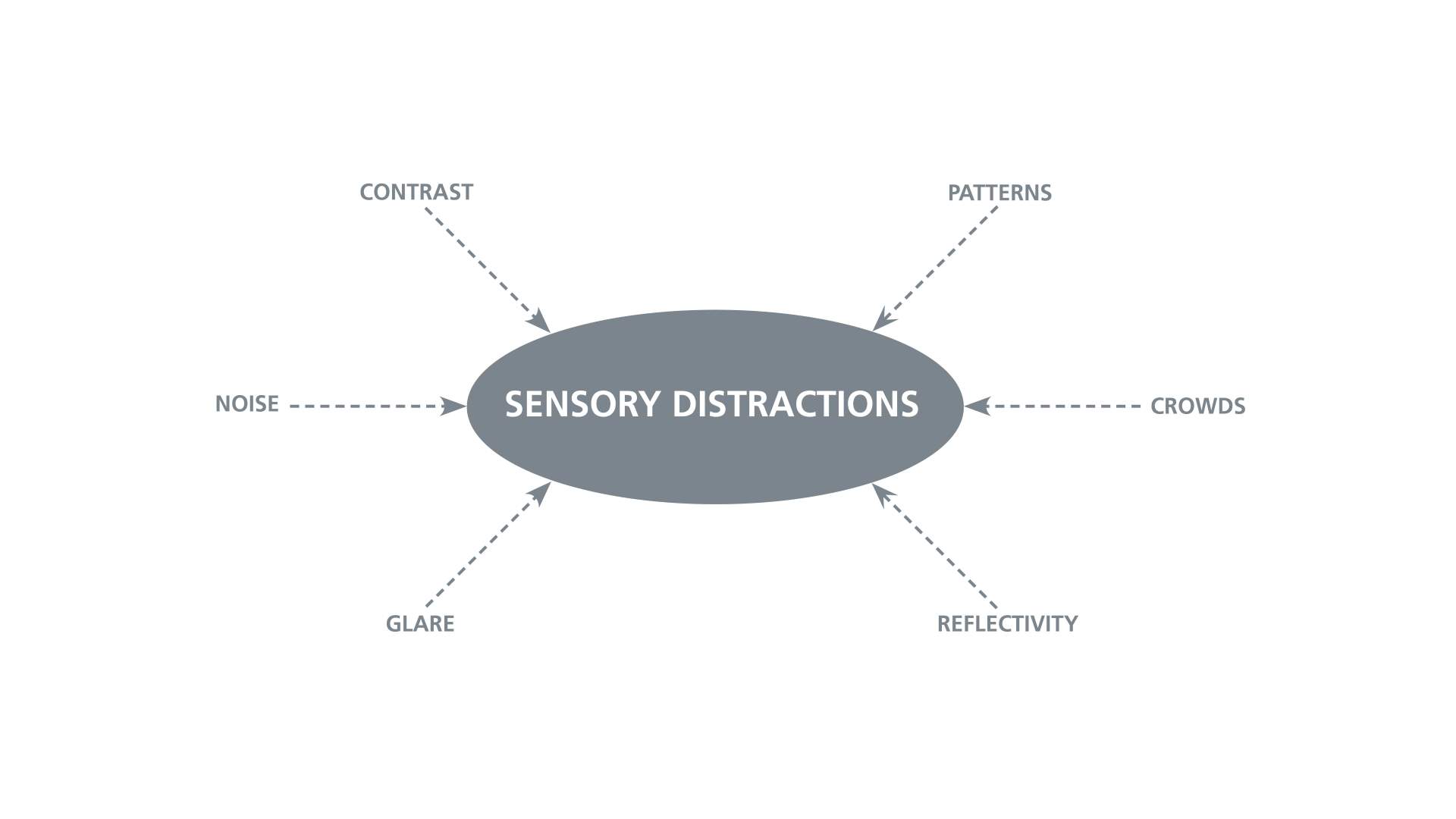

As architects striving to create inclusive spaces in which everyone can thrive, we must consider the implications of a neurodiverse population. Specific environmental conditions – particularly those causing distraction and anxiety – often affect neurodiverse learners or staff members more significantly. Mitigating sensory distractions such as visual contrast, reflectivity, noise, and large crowds are critical approaches for addressing neurodivergence in the built environment. Key design strategies include:

- Low-stimulation, quiet environments for focus

- Avoidance of highly reflective and bright finishes

- Layout and furniture to indicate purpose

- Distinct, identifiable community areas

- Avoidance of intense patterns

- ‘Zone-finding’ by way of material applications

- Occupant control of lighting levels

In addition to controlling sensory distractions, just as critical is providing users with the agency of choice. Like other design strategies supporting inclusion, environments that offer occupants a choice in the setting in which they feel most comfortable is paramount. “One size fits all” is no longer a productive model, as we have seen in the recent evolution of classroom and workplace design. For neurodiverse students and staff, this does not mean creating a sea of mobile, flexible furniture configurations that can be endlessly rearranged, but controlling environmental factors to mitigate distraction and anxiety. We promote the concept of “fixed variation” — offering personal choice and predictability through distinct spaces and finish/furniture arrangements.

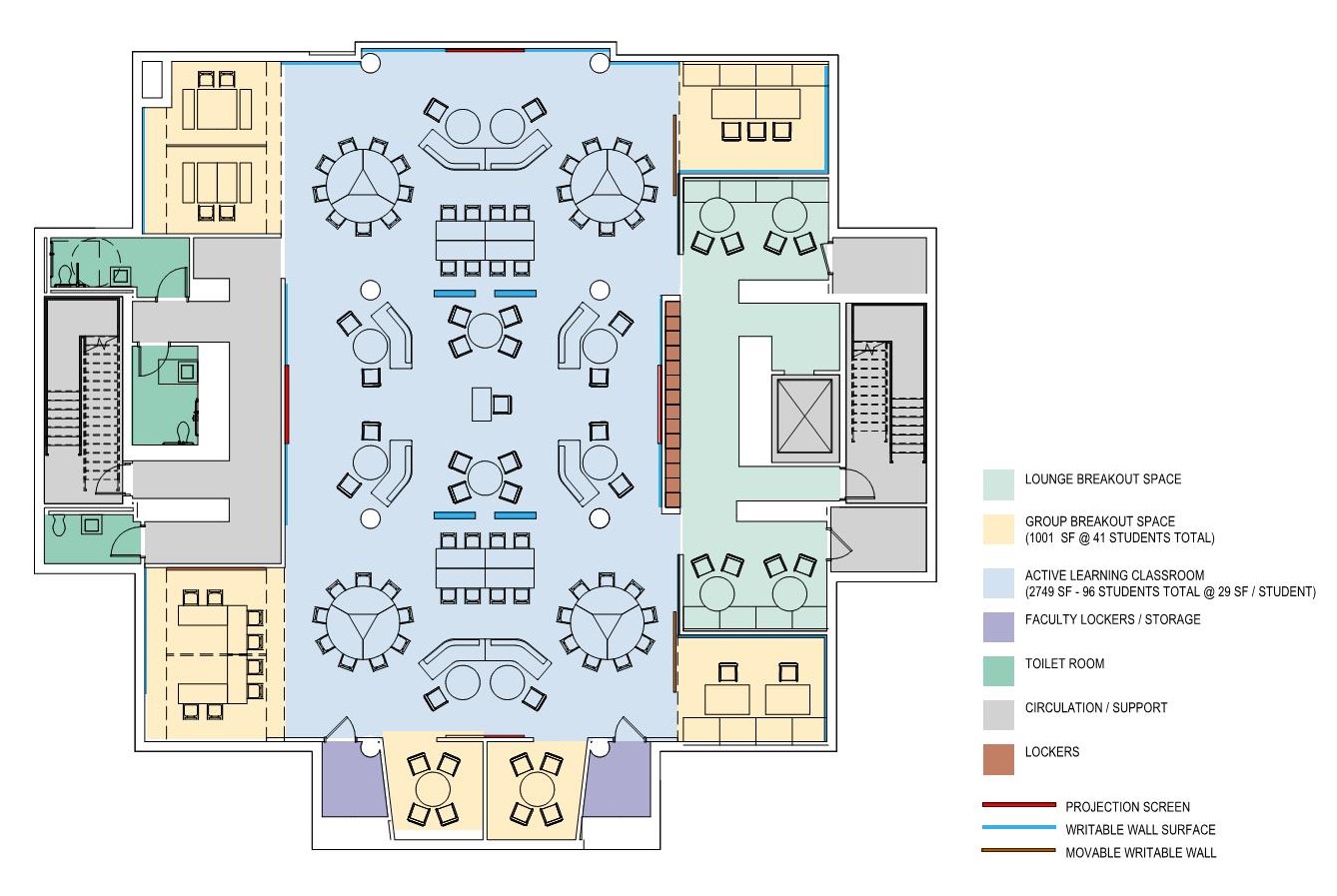

Environments of fixed variation will offer a range of spatial qualities and furnishings that support the central program (classroom, office, meeting space, etc.). Often, these spaces will feature types of breakout areas at a smaller scale to support individuals and small groups that prefer to learn or work in a less open, distracting environment. By leveraging technology, these breakout spaces can operate simultaneously as the main space. Additionally, spaces supporting fixed variation typically will feature many choices for seating – casual arrangements, traditional desks, multiple-height tables, and options for group and individual settings. Design to support neurodiversity builds upon this spatial variety with sensitivity to addressing common sensory distractions. Controlling background noise and improving speech clarity with mechanical and finish solutions is important. A palette of interior materials that is subtle can help identify zones within the space to aid in wayfinding. Additionally, providing a level of user control of elements, such as lighting levels and enclosure, help spaces respond to personal preference.

Fixed Variation: Neurodiversity classroom concept.

As inclusivity takes a stronger position in cultural and design discourse, we see a variety of emerging spatial environments to promote user choice and a sense of belonging. Workplace design is increasingly moving away from ubiquitous, open-office space towards planning to provides discrete zones to support a variation of tasks, collaboration, and user preference. Academic spaces – already trending towards active-learning models – are evolving from large-scale tiered lecture halls to smaller, varied zones within a single room that allow for group collaboration and individual preference. By designing spaces that accommodate a variety of work styles, personality types and abilities, we provide environments in which everyone can find a place.

While neurodiversity remains a somewhat new concept within architectural design, it is important to consider the needs of this unique population. Good design has the power to create better outcomes – this is why design matters! By focusing on the impacts environmental factors have on people, we can create inclusive spaces that people want to experience and help us all thrive in our pursuits. Companies and institutions of learning need to ensure their most valuable asset – people – are in spaces where ALL can flourish.