The diagram, in architecture, is a representational means of expressing the ideas, elements, relationships and structures that influence organization. The roots of the diagram in architecture can be traced back to the introduction of the parti pris (eventually shortened to “parti”) during the 19th century by the L’Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris, France. The parti, which translates to “departure point,” is meant to capture the big idea that precedes the development of formal architectural drawings. Since the 1980s, the diagram – as opposed to the drawing or model – has evolved into the preferred vehicle for communicating the forces that shape architectural design. A diagram can manifest in many different types (planimetric, sectional, sequential, etc.) that allow for suggestive representations of things such as structure, context, program, performance and form.

At Amenta Emma, the diagram is a crucial tool in our design process to promote clarity. We believe that successful architecture clearly expresses the overarching idea behind its organization, from the broad gesture to the fine details. For us, the diagram provides two key utilities: to distill the big idea into clear and simple terms and to serve as reference point for decisions throughout the advancement of a project. By distilling the concepts behind a project to their essence, we can use the diagram to test various manifestations of those concepts for legibility and support of the project’s goals during the design process. The diagram allows team members to ask the simple question throughout the development of a project: does this decision reinforce the diagram or not?

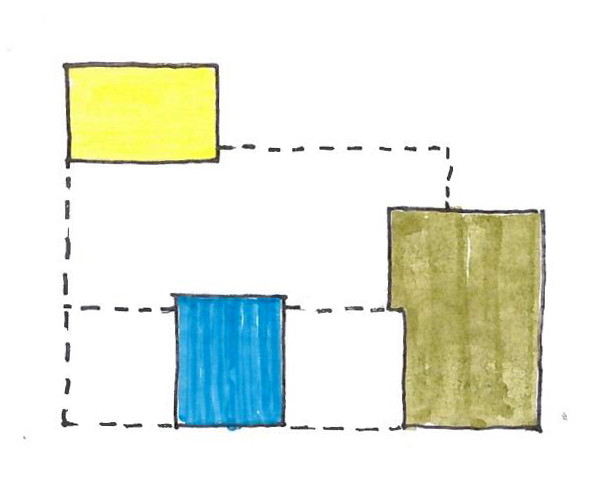

Student Advising Commons at Quinnipiac University

When designing a new Student Advising Commons at Quinnipiac University, we utilized the diagram to establish relationships between program and spatial elements. Program spaces for meeting were represented as individual volumes inserted within a larger volume, creating a colorful interior and offering a clear relationship of parts to the whole. As this project advanced through drawing and construction stages, our team was always returning to the simplicity of the initial diagram for guidance in reinforcing the design intent. The result was a simple, rational space that was free from extraneous gestures or details that would have muddied the clarity of the initial diagram.

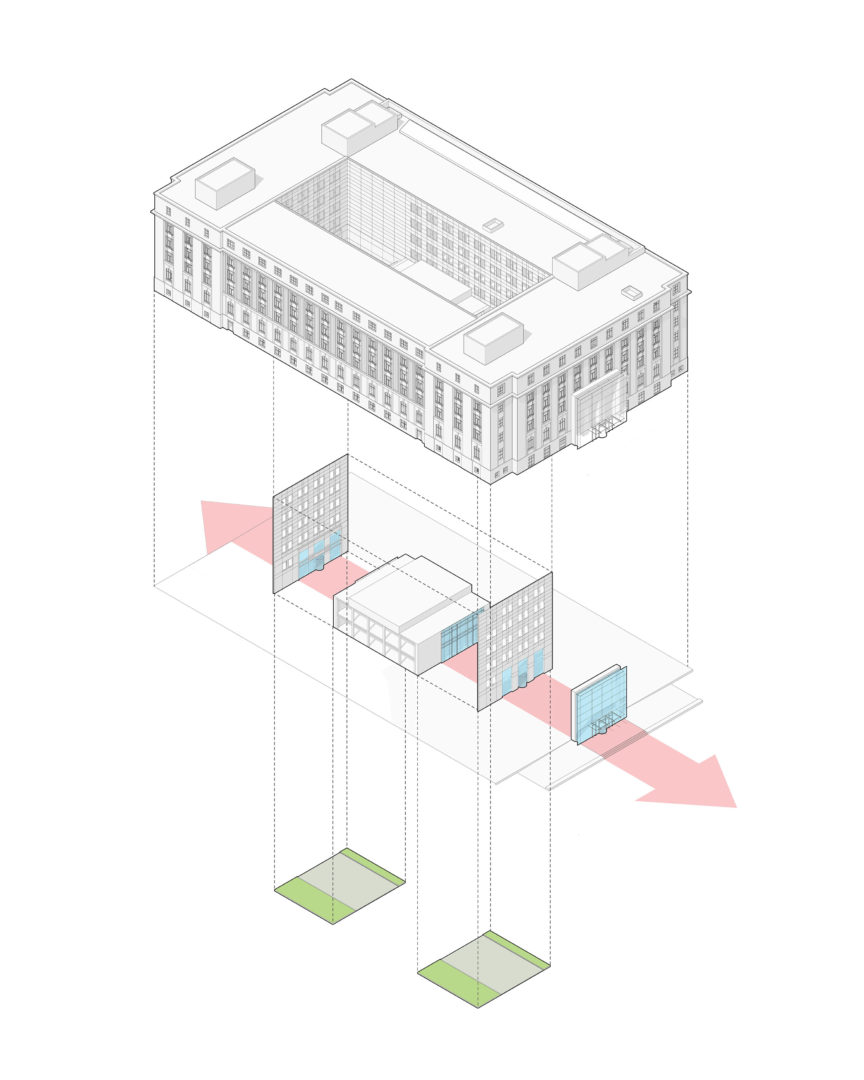

Sometimes we deploy the diagram in ways that favor identifying the big concept that will drive the organization rather than defining the organization itself. This was true in the case of the renovation of the Connecticut State Office Building – a heavy neo-classical structure from the early 20th century that featured a nearly forgotten courtyard space. As our design team sat about the approach to designing the renovation, they quickly understood the necessity of introducing visual transparency through the building in order to activate the courtyard. An early diagram was created that expressed this idea, showing the continuity of view from entering the building, through the interior and onto the courtyard. This shift, from opaque container to open, daylit building, was a powerful and legible idea that the client could easily understand and was central to their goals for the renovation.

Connecticut State Office Building at 165 Capitol Avenue – Hartford, CT

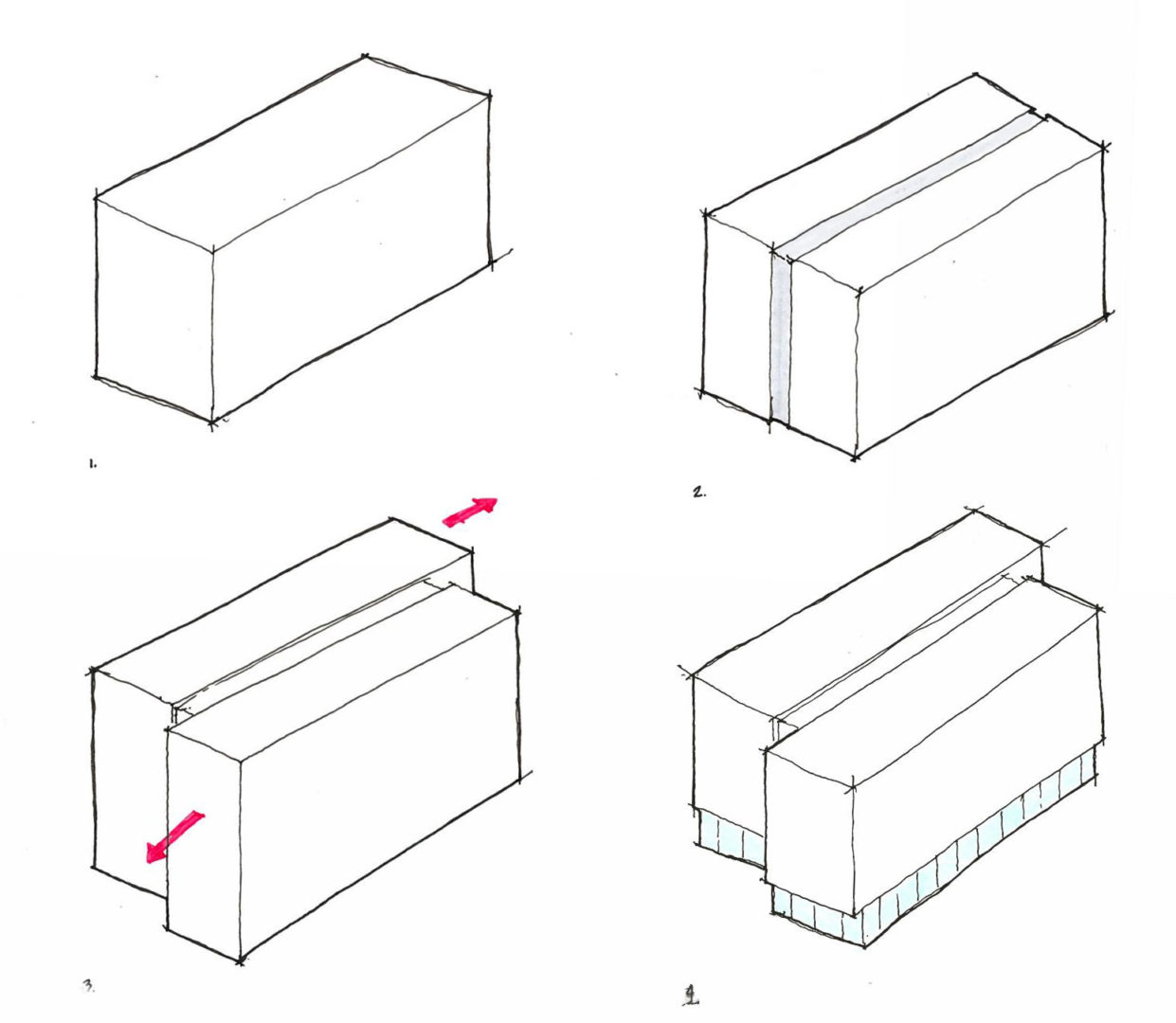

Another way we have utilized the diagram is to express the hierarchy of large-scale gestures in the design of buildings. As is often the case, there are many different elements and, at times, voices, that compete for influence in the final realization of a building or interior space. The diagram is very useful in establishing the legibility of the ‘broad stroke’ when designing a building’s mass and exterior expression. For the design of a new multi-family building set in an urban context in West Hartford, we utilized the diagram to communicate our design process to our client and local approval agencies. In this case, the diagram explained the evolution of the building mass from simple container to a building form that responded to the program. We find the use of ‘procedural’ diagrams – drawings that clarify the influencing factors that shape how buildings are expressed in a series of steps – are especially useful tools for our clients and design teams alike.

540 New Park Avenue – West Hartford, CT

As we tackle larger and more complex projects each year, the diagram remains at the core of the Amenta Emma design process. Our clients often come to us with a clear idea of how they want something to work or feel; our job as designers is to express that vision in their built environment. Using diagrams to distill the complex into the simple allows the big idea to be understood by all involved on the design team and, most importantly, promotes clarity of our client’s aspiration in the finished product.